Network Analysis Shows Previously Unreported Features of Javanese Traditional Theatre

The methods of network analysis are becoming increasingly relevant to the digital humanities, particularly in relation to the study of literary characters (Moretti 2011; Pohl, Reitz, and Birke 2008; Park et al. 2013; Trilcke, Fischer, and Kampkaspar 2015; Elson, Dames, and McKeown 2010; Agarwal et al. 2012; Waumans, Nicodème, and Bersini 2015; Xanthos et al. 2016; Choi and Kim 2007; Bollen 2017; Fischer et al. 2017). Several recent studies and presentations have focused on drama. Most studies deal with European and American drama and this is possibly due in part due to easily available data.

However, we believe that network analysis can be used to interrogate interesting features of Javanese theatre as well. Our research focuses on

wayang kulit

(shadow puppetry), one of the oldest and most respected traditions of Southeast Asia. A typical performance lasts all night but usually focuses on a small episode of the Mahabharata, one of the two major Sanskrit epics of Ancient India that provides the narrative material for many traditional theatre forms in Southeast Asia. There are no comprehensive storylines or transcripts available in digital form, so we created our own database by digitizing and annotating the authoritative list of

wayang kulit

storylines compiled by Purwadi (2009).

We used the resulting data to construct a weighted, undirected co-occurence network at the

adegan

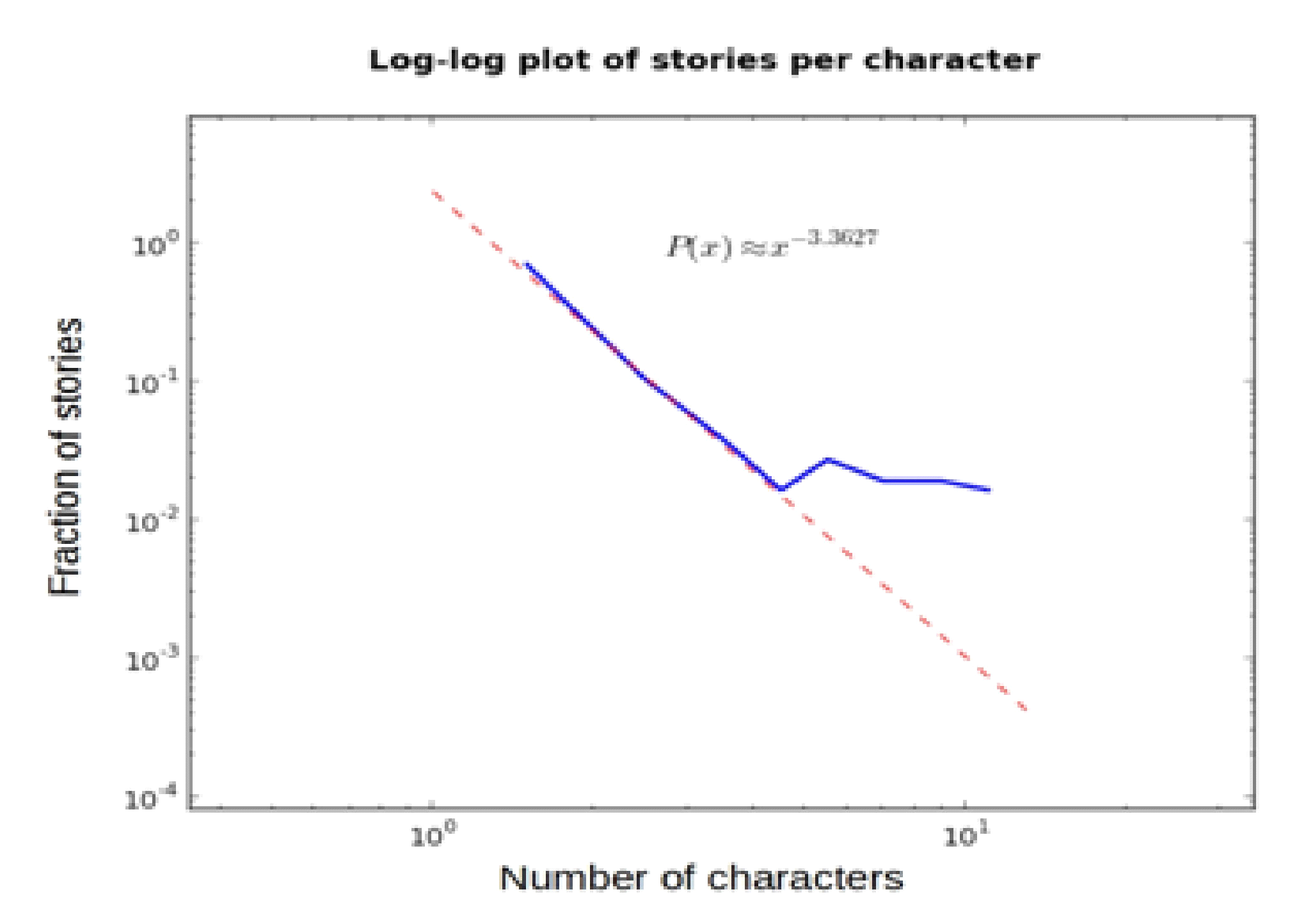

(scene) level. Each character is modeled as a node. An edge between two characters means they are present at the same scene, regardless of whether they interact with each other. The weight indicates the number of scenes in which both characters are simultaneously present. While certain favorite characters appear in many stories, many other characters are only present in one storyline. Thus, the network exhibits the ubiquitous characteristics of real-life social networks (Carrington, Scott, and Wasserman 2005; Knoke and Yang 2008). These include a high-level degree of heterogeneity (the number of stories per character in a bipartite projection decreases according to the distribution

P(x)

≈

x

-3.3627

, see Figure 1) and small world properties:

- A low clustering coefficient (0.863)

- A low average shortest path (0.86)

Figure 1

. Log-log plot of stories per character in the wayang network (right). The solid lines represent the actual distribution and the dashed line the theoretical power-law distributions.

Characters in Euro-American theatre usually appear in only one play (or at best in a handful of plays) and the kind of structural analysis we conducted here is only possible in a narrative tradition with recurrent characters. We thus feel this contributes an interesting case study to the burgeoning field on network analysis of theatre characters. Beyond merely revealing some interesting quantitative (small-world) properties of this network, further quantitative analysis enabled us to identify previously unreported features of the

wayang

tradition: 1) a network-theoretical perspective reveals some unexpected insights into how various indigenous Javanese elements were integrated into the «structure» of the original Indian epic and 2) there are significant differences in the network properties of characters that can be represented by «interchangeable» puppets and those that can not be changed. To fully appreciate the significance of these findings, a quick overview of the history and performance conventions of

wayang

is needed.

In Java (Indonesia), the recorded history of Mahabharata-derived performances dates back to the 10

th

century CE, but the performances might have an older history (Escobar Varela 2017). In any case, over this one-thousand year period, Javanese artists have invented a number of new characters and local storylines that they have interwoven with the original Sanskrit epics. However, people still readily acknowledge the stories to be mostly Indian in origin. Much to our surprise, we found out that almost half of the characters used in performance today are local in origin. Our initial estimate (and that of people informally interviewed), put the number of local Javanese characters at only 20% to 30%. Why the discrepancy? By applying network theoretical measures, we found significant differences between the Javanese and the Indian characters. Except for the

punokawan

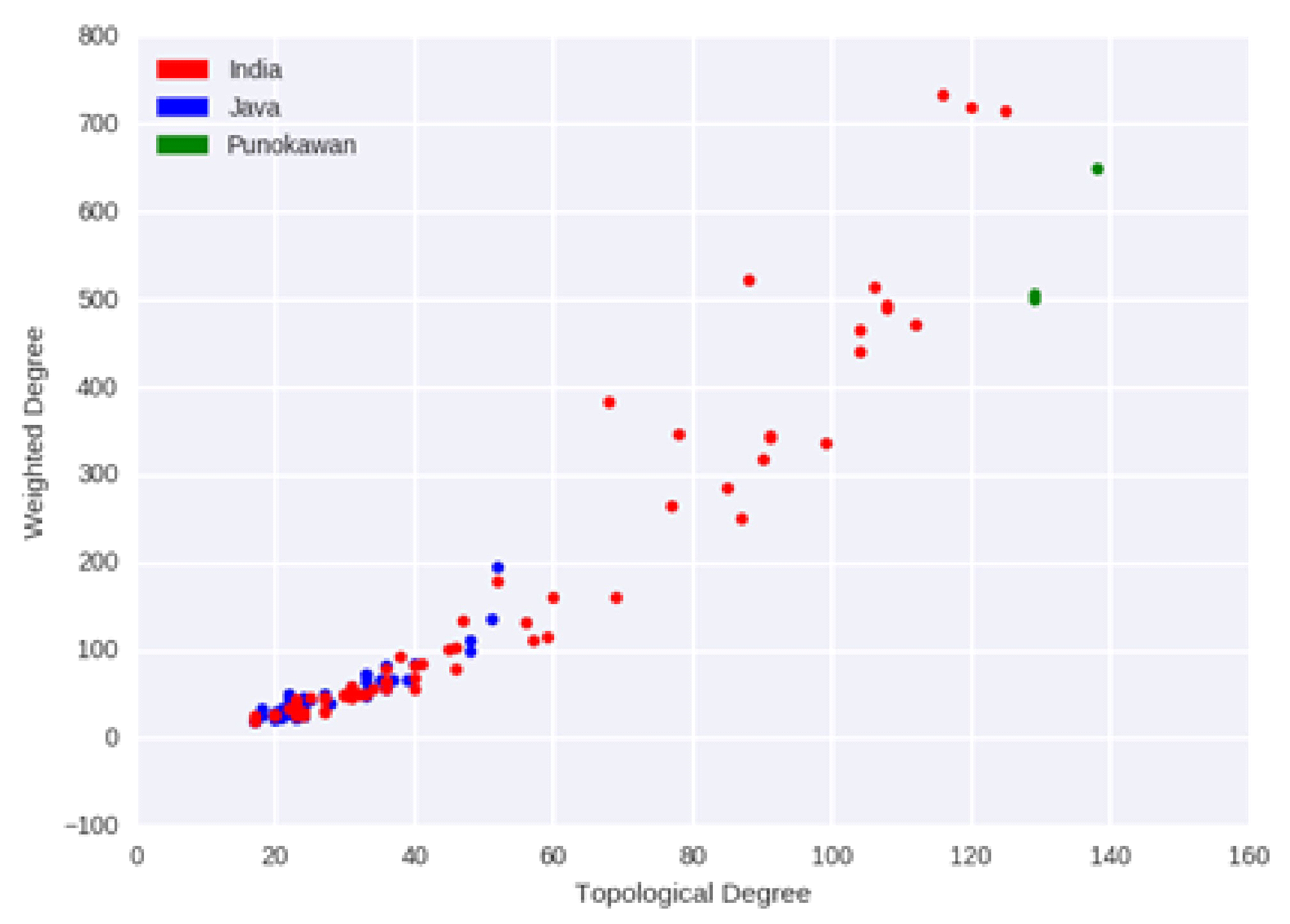

(the clown-servants), which appear in almost every story, all local Javanese characters have low values for network-theoretical measures such as topological degree and weighted degree (Figure 2). We hypothesize that the reason why people think Javanese characters are less prevalent than they truly are is that, on average, Javanese characters are significantly less «important’ in terms of their network-theoretical measurements.

Figure 2

. Weighted degree and topological degree of Javanese, Javanese

punokawan

(clown-servants) and Indian characters.

Our second finding relates to the usage of the puppets in performance. A complete set of puppets can be expensive and often the the

dalang

(puppeteer) would not have all the needed puppets for a given performance. In this case, they have a choice: they can either borrow a puppet from another

dalang

, or they can substitute the required puppet for one that they already posses in their collections. This choice is based on weather the character is considered as «interchangeable» or not. We noted the interchangeability of characters based on interviews with professional

dalang.

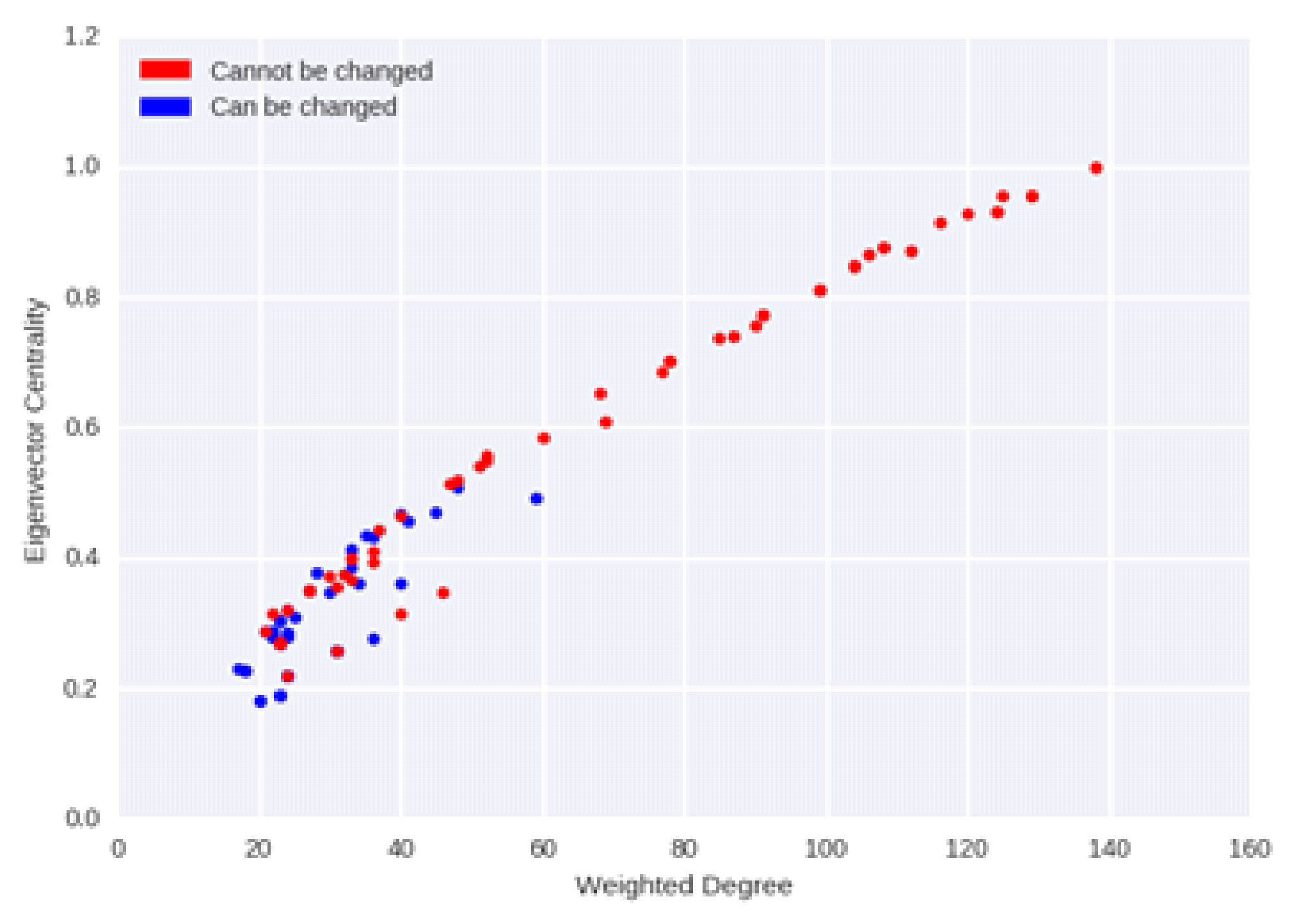

When comparing the network-theoretical measurements against this table, we also found that all characters deemed interchangeable have low eigenvector centrality and weighted degree in our network (Figure 3). In other words, the more important a character (in network-theoretical terms), the less likely it is to be exchanged for another character.

Figure 3.

Eigenvector centrality and weighted degree of interchangeable and non-interchangeable characters.

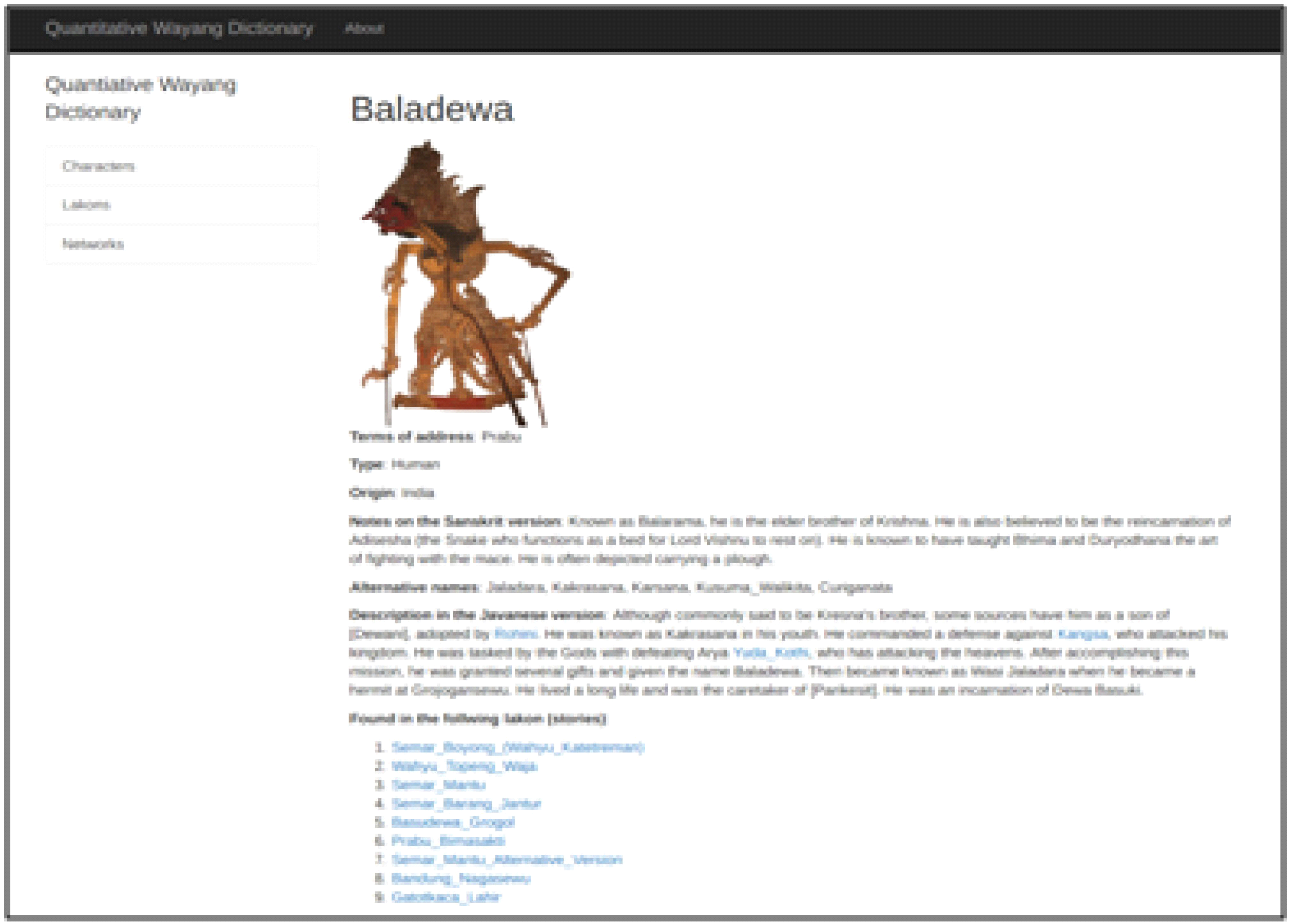

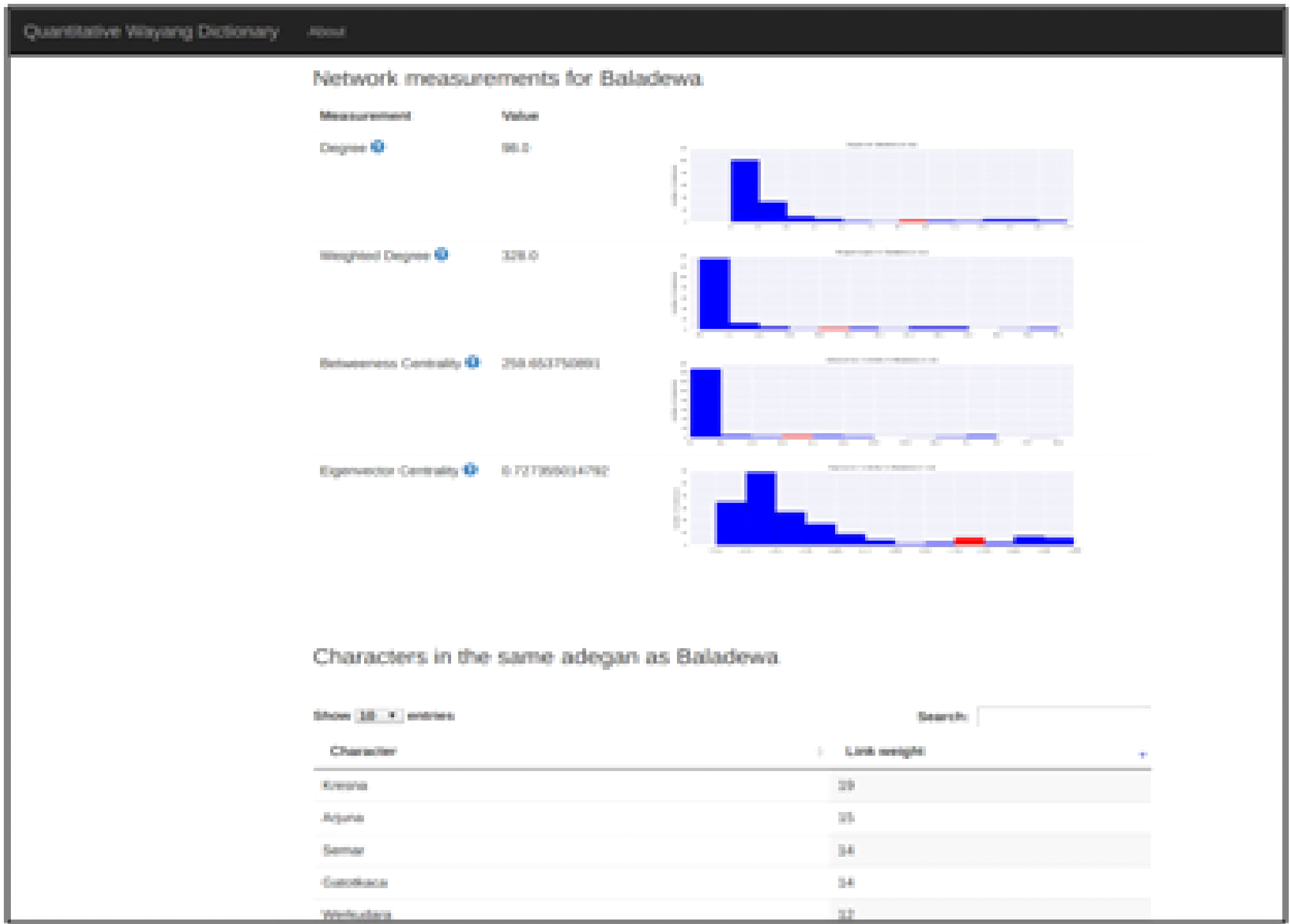

Both of this findings seem logical in retrospect, but they were previously unreported. We hope that this application of network analysis can add to the field of network analysis of literary characters and also contribute to the scholarship on Javanese theatre. For this purpose, we are developing an interactive online portal where the contextual information for each character (Figure 4) and the values for network-theoretical measures for each character (Figure 5) and can be consulted in greater detail. All datasets will be openly available for download and we hope this will encourage other research teams to contribute to the quantitative analysis of Javanese theatre.

Figure 4.

Contextual information for a given character (Baladewa in this example), forthcoming online portal.

Figure 5.

Network-theoretical measures for a given character (Baladewa in this example), forthcoming online portal.

Appendix A

- Bollen, Jonathan. 2017. “Data Models for Theatre Research: People, Places, and Performance.”

Theatre Journal 68 (4):615–32. https://doi.org/10.1353/tj.2016.0109. - Carrington, Peter J., John Scott, and Stanley Wasserman. 2005.

Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis. Vol. no. 28. Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Choi, Yeon-Mu, and Hyun-Joo Kim. 2007. “A Directed Network of Greek and Roman Mythology.”

Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 382 (2):665–71. - Elson, David K, Nicholas Dames, and Kathleen R McKeown. 2010. “Extracting Social Networks from Literary Fiction.” In

Proceedings of the 48th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 138–47. Association for Computational Linguistics. - Escobar Varela, Miguel. 2017. “From Copper-Plate Inscriptions to Interactive Websites: Documenting Javanese Wayang Theatre.” In

Documenting Performance: The Context and Processes of Digital Curation and Archiving, 203–14. London and New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. - Fischer, Frank, Mathias Göbel, Dario Kampkaspar, Christopher Kittel, and Peer Trilcke. 2017. “Network Dynamics, Plot Analysis: Approaching the Progressive Structuration of Literary Texts.” In

Digital Humanities 2017 (Montréal, 8–11 August 2017). Book of Abstracts. - Knoke, David, and Song Yang. 2008.

Social Network Analysis. Vol. 154. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. Los Angeles: SAGE. - Moretti, Franco. 2011. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.”

New Left Review, no. 68(March):80. - Park, Gyeong-Mi, Sung-Hwan Kim, Hye-Ryeon Hwang, and Hwan-Gue Cho. 2013. “Complex System Analysis of Social Networks Extracted from Literary Fictions.”

International Journal of Machine Learning and Computing 3 (1):107. - Pohl, Mathias, Florian Reitz, and Peter Birke. 2008. “As Time Goes by: Integrated Visualization and Analysis of Dynamic Networks.” In

Proceedings of the Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces, 372–75. ACM. - Purwadi. 2009.

Kempalan Balungan Lakon Wayang Purwa. Surakarta: Cendrakasih. - Trilcke, Peer, Frank Fischer, and Dario Kampkaspar. 2015. “Digital Network Analysis of Dramatic Texts.” In

DH2015 Conference Abstracts. Sydney, Australia. Vol. 1184. - Waumans, Michaël C, Thibaut Nicodème, and Hugues Bersini. 2015. “Topology Analysis of Social Networks Extracted from Literature.”

PloS One 10 (6):e0126470. - Xanthos, Aris, Isaac Pante, Yannick Rochat, and Martin Grandjean. 2016. “Visualising the Dynamics of Character Networks.” In

Digital Humanities 2016: Conference Abstracts, 417–19.